AUSTRALIA

A Snapshot

ACOSS, the Australian Council of Social Services, which is a peak body for the community and social service sector in conjunction with the the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of New South Wales produce regular reports, Poverty in Australia. The key findings of it’s most recent report in 2022 included:

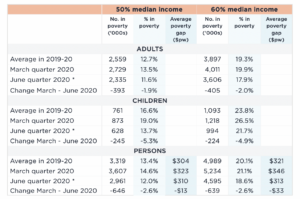

- The poverty line (50% of median income) for a single adult was $489 a week. For a couple with 2 children, it was $1,027 a week.

- 3,319,000 million people (13.4% of the population), were living below the poverty line, after taking account of their housing costs.

- 761,000 children (16.6% of all children) were living below the poverty line.

- Child poverty in Australia rose from 16.2% in the September quarter of 2019 to 19% in the March quarter of 2020. It then fell to 13.7% – a two-decade low – in June 2020.

- Boosted income support pushed weekly social security payments for single adults with no private income from $134 below the poverty line to $146 above it. Single parents with two children went from $119 below to $176 above the poverty line.

- Couples with no children went from being $152 below to $411 above the poverty line while couples with two children went from being $187 below the poverty line to $361 above it.

What is Poverty?

There are varying definitions in use across the world and in Australia. Poverty can be calculated as a measure of income or wealth, using ‘poverty lines’; or by looking at what essential items people are missing out on through lack of income, or by having to spend more of their income on certain costs above others. For example, spending on housing and utilities instead of food. This is known as ‘deprivation’.

The ACOSS Poverty in Australia 2022 report uses the internationally accepted poverty line, defined as 50% of median household income, and adjusts for housing costs. This is the poverty line used by the OECD.

In Australia, a very common and popularly known measure was the ‘Henderson Line’; a monetary figure produced by the Melbourne Institute quarterly that measured income to need in reference to a basic or austere standard of living. Anyone living below that line was considered to be in poverty. Changing demographics, especially in the family, have seen a move away from this standard to the one described above.

However, as Australia’s Bishops have commented in a series of Social Justice Statements over the last thirty years, poverty is much more than just a lack of income. Poverty is an experience, felt by real human beings and that experience is a complex web of persistent deprivation, social exclusion and marginalisation.

The Dropping off the Edge study is a good indicator of the kinds of correlated issues and experiences that can add up to an overall experience of poverty beyond only financial. It studies geographical location of poverty and disadvantage based on a range of factors. You can explore their study as well as find your Local Government Area profile here.

Who Experiences Poverty?

Aside from the general overview of poverty in Australia outlined above there are a few specific groups of people who bear the injustice of poverty more acutely than others. Children under 15 and people over 65 have generally had the highest poverty rates, but for the older group these rates have declined in recent years, probably reflecting the higher pension payment compared to Newstart.

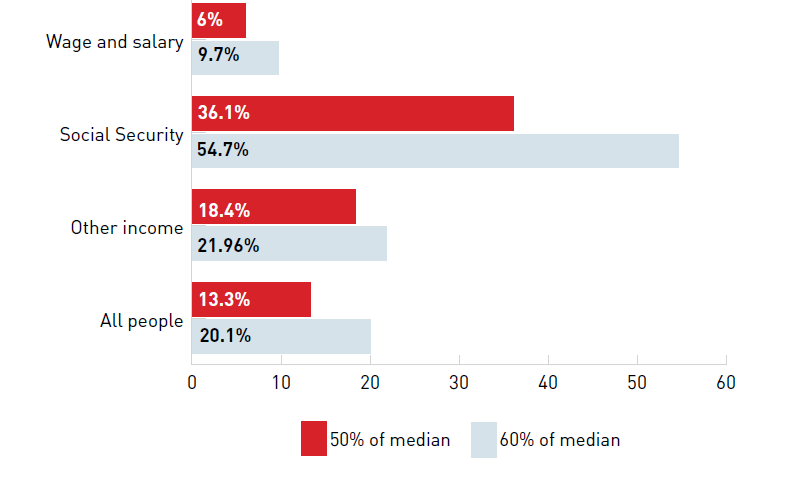

One key factor often tying these groups together is that they rely on social security payments as their sole source of income. Anyone in this position is far more likely to experience poverty as all the various payments are below the poverty line and increasingly so as they do not keep pace with cost of living, especially the steeply rising costs of housing.

Because relying on social welfare payments is usually the result of other factors that keep people from work or burden them with other disadvantage there are particular groups who are persistently over-represented in studies of poverty in Australia. The Productivity Commission Report calls this ‘multiple deprivation’ and highlights lone parents, children, Indigenous Australians and people living with disability as especially prone to complex disadvantage.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders

Noting the absence of some key statistical studies, the ACOSS study of Australian poverty showed that Aboriginal and Torrres Strait Islanders are more likely to experience poverty and are less likely to ‘exit welfare’ than other Australians.![]()

Unemployment is a key reason for welfare payments being the main source of income. In 2016 only 46% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders aged over 15 years were employed and only 27.7% in full time work. While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders make up only 3% of the population they represent 9.6% of those receiving Newstart, 14.3% of those receiving the Parenting Payment and 18.9% of those accessing Youth Allowance. Further contributing to welfare reliance is that fact that almost 45% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders over 15 years of age experience disability. Non-Aboriginal people with disability suffer poverty, often due to employment exclusion, at higher rates so being both Indigenous and having a disability is a double bind.

Women and children

Women tend to experience poverty at higher rates due to being in lower paid work, being unemployed in paid work due to caring responsibilities and for disproportionately assuming sole parenting duties upon the end of a relationship. In this situation single mothers often rely entirely on social security payments as their sole source of income and like all other people in this category are subjected to living below the poverty line because these payments are manifestly inadequate, especially in the face of the rapid increase in housing costs over the last decade or so. You can find a discussion and breakdown of social security payments in the ACOSS Report.

One in six (17.4%) of children under the age of 15 lives in poverty. Source and image: https://www.acoss.org.au/poverty/

The flow-on effect of women living in poverty is children living in poverty. In 2016 roughly 17% or 731 300 children were living in poverty in Australia. Those most at risk are children in lone parent families, who are more than three times likely to be living in poverty (40.6%) than those from couple families (12.5%). Since 2012, the poverty rate for children in lone parent families has gone up from 36.8 to 40.6%. Compounding this is the cost of housing and the fact that those living in rental property represent more disadvantage than those in the home-owner category. The vast majority of people below the poverty line are in rental housing (59.7%), with most in private rental housing (44.2%). Only 15.5% of people living below the poverty line were home-owners.

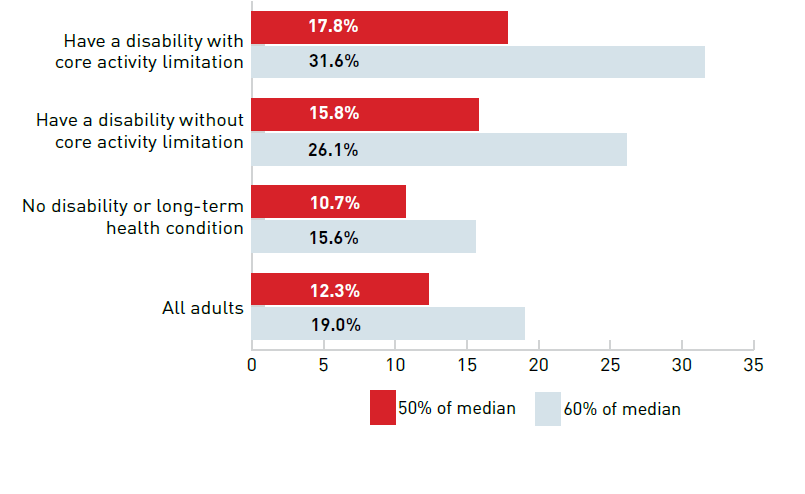

People with Disability

ACOSS notes that in 2013-14, 510 900 (15.8%) adults with a a disability and a further 328 100 people with a core activity limitation were living below the poverty line. (A core activity limitation involves a profound, severe or moderate limitation with core activities – communication, self-care and mobility). This higher risk of poverty is likely to be due to the greater difficulty people with disability have in finding and maintaining employment, therefore relying heavily on income support payments. They often have to stretch these payments further too as they frequently incur costs associated with managing their disability.

What Causes Poverty?

Most immediately a lack of money causes poverty. But is is the circumstances underlying that financial lack that are the drivers of poverty, and those circumstances are varied and complex.

It is all too common to hear poverty blamed on the decisions and lifestyle of the person experiencing it. While we cannot negate each person’s need to take personal responsibility for themselves, all the research shows that the main drivers of poverty are beyond individual control and deeply rooted in social, economic and political systems and structures geared towards keeping and putting people into poverty. This is especially so if people experience more than one risk factor for poverty, such as being a woman and living with disability.

In this regard there is not one simple cause of poverty but an entangled knot of causes that grow from decisions we collectively make about things like how are economy is structured, the kinds of labour conditions we create, the regulation and tax settings we create in all kinds of markets like the housing sector that disadvantage the poorer and more vulnerable amongst us. And as the statistics above show our decisions about what kind of social welfare system we will have, and our beliefs about the character of people accessing it has created a punitive, degrading set of payments that fall well below the poverty line.

These unjust structures persist not because there are no solutions but because of our cultural values and these often have long histories. Take, for example, the multi-generational poverty experienced by Indigenous Australians which is directly correlated to the systematic racism and disenfranchisement they have been subjected to for the last 200 or so years. Similarly, longer histories of devaluing and marginalising people with disability has helped to create a culture which is still too often resistant to employing people with disability or creating a social safety net that adequately meets their needs to live a dignified, self-directed life.

Though we have seen progress in some of these areas, the real work of reducing poverty lies in changing our beliefs about what it means to be poor, about what it means to be a community and then changing our systems, infrastructure and policies in ways that reflect a belief in the inherent dignity of every person. Ultimately, the hard work of eradicating poverty doesn’t lie in policy settings, but in changing the way we value human beings.

For deeper discussions on the structural causes and experiences of poverty see:

Church Context:

- Australian Catholic Bishops Conference (ACBC), ‘Everyone’s Business: Developing an Inclusive and Sustainable Economy’, Social Justice Statement 2017-18.

- ACBC, ‘Lazarus at our Gate: A Critical Moment in the Fight Against World Poverty’. 2013-14.

- ACBC, ‘A New Beginning: Eradicating Poverty in Our World’, Social Justice Statement.’ 1996.

- ACBC, ‘Common Wealth for the Common Good’, Social Justice Statement 1992.

Broader Context:

- Poverty in Australia 2022 Report.

- Melbourne Institute, Economic and Social Disadvantage Research Project.

- Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW, Measures of Social Inequality and Wellbeing.

- Anti-Poverty Week, Poverty in Australia.

GLOBALLY

As in the Australian context, poverty is not just a lack of income and resources to ensure a sustainable livelihood, though that is the primary cause, it is also the systemic choices we make that ultimately manifest (and, in turn make worse) that lack of income. These include hunger and malnutrition, limited access to education and other basic services, social discrimination and exclusion as well as the lack of participation in decision-making.

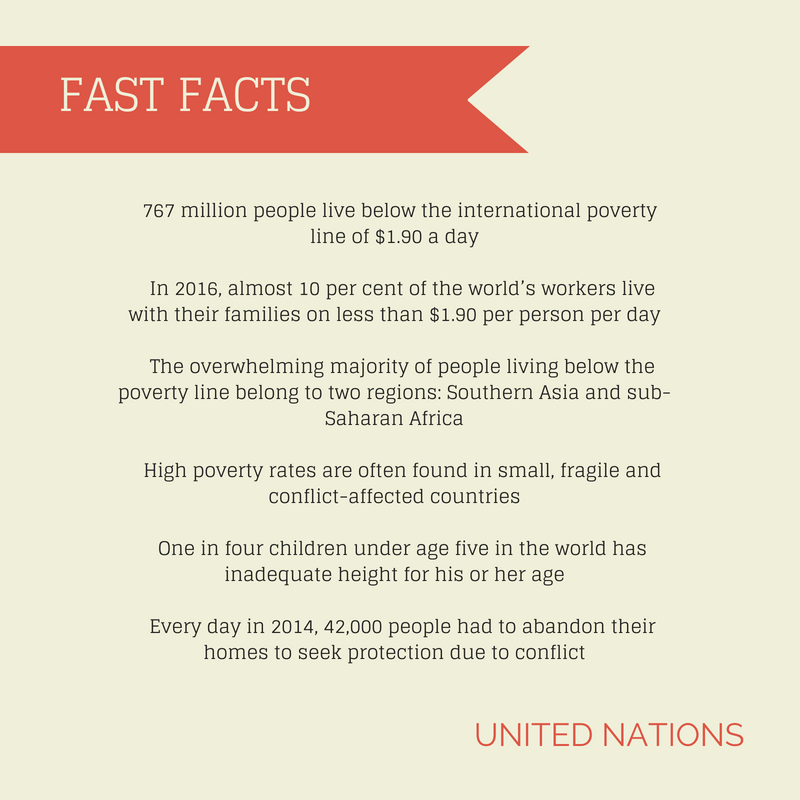

According to the United Nations, extreme poverty rates have been cut by more than half since 1990. While this is a remarkable achievement, one in five people in developing regions still live on less than $1.90 a day, and there are millions more who make little more than this, and many people risk slipping back into poverty all too easily.

A lack of national income corresponds to higher poverty rates. Also note how most of our Pacific neighbours have far lower levels of income, and corresponding poverty, than Australia.

While there is a complex web of factors that contribute to a country’s Gross National Income (GNI), and its potential to raise it, one key element is the reduction or forgiveness of debt for impoverished countries for whom those payments contribute to poverty. Relieving that debt in the first instance frees up spending for the range of services and infrastructure that could alleviate the immediate realities of poverty. And in the second instance, over time, it allows investment into programs, employment, education and industry that supports business growth and investment that can create long-term sustainable change. Another part of the picture is international aid.

Australian Aid

There are any number of reasons for wealthy countries, like Australia, to provide foreign aid. Many argue it is simply a moral duty, especially for rich countries, to offer the help needed to save lives, end cycles of violence, poverty, poor health outcomes and entrenched disadvantage. Others add that it is a stabilising political force that opens trade routes and potentially stable, open, democratic governments, which benefits donor countries as much as recipients. Those with a more historical perspective argue that much of our wealth and prosperity has come from, and indeed continues to, from the colonisation, domination and exploitation of other countries. Aid, then, is not so much an obligation as reparation.

For whatever reasons, and in acknowledgement of its failures and limitations, there is little disagreement that foreign aid is a necessary piece of the puzzle in alleviating world poverty. In that regard, by international standards Australia is not doing its fair share.

Australian Aid makes up about 0.72% of overall budget expenditure but since 2022.

- To find out what you can do to help eradicate poverty click here.

- To get a sense of what the Church says about poverty click here.

- To learn more about inequality, which is connected to poverty, click here.