What is the current situation?

The Global Situation

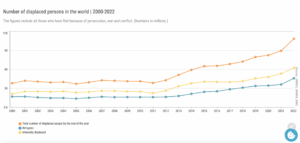

In 2023 there is the highest levels of displacement on record. An unprecedented nearly 108.4 million people around the world have been forced from home, nearly 62.5 million of whom are internally displaced persons. Among them are nearly 43.3 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18.

According to Amnesty International, over 1.19 million women, men and children need to be resettled in a safe country, yet only 30 countries offer just over 100,000 annual resettlement places and this figure has not changed in the last several years despite the increase in need.

According to Amnesty International, over 1.19 million women, men and children need to be resettled in a safe country, yet only 30 countries offer just over 100,000 annual resettlement places and this figure has not changed in the last several years despite the increase in need.

According to Amnesty, 65.3 million people worldwide had been forced to leave their homes as a result of conflict, persecution, violence and human rights violations. Of these:

Right now, the vast majority of the world’s refugees live in developing regions, with half of the 20 million refugees in just 10 countries.

National Situation

Many people come to Australia seeking asylum from persecution in their country of origin or residence. People who seek asylum are not acting illegally because they have a human right to seek asylum under Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, regardless of how they arrive in Australia or whether or not they have a valid visa when they do. Australia has also ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention under which it has an obligation to assess asylum seekers applications for protection. However, both the current Australian Government and past government’s policies towards people seeking asylum and refugees are far removed from the Convention’s requirements and perpetuate multiple, serious human rights violations.

The Australian Human Rights Commission has recognised: “Australia has obligations to protect the human rights of all asylum seekers and refugees who arrive in Australia, regardless of how or where they arrive and whether they arrive with or without a visa.

The Australian Human Rights Commission has recognised: “Australia has obligations to protect the human rights of all asylum seekers and refugees who arrive in Australia, regardless of how or where they arrive and whether they arrive with or without a visa.

As a party to the Refugees Convention, Australia has agreed to ensure that people who meet the United Nations definition of refugee are not sent back to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened. This is known as the principle of non-refoulement.” However, Australia’s treatment of people seeking asylum does not meet these conditions at all. Dozens of people seeking protection that Australia has deported back to their home country have faced, threats, persecution violence and have been killed. In January 2021 at Australia’s Third Universal Periodic Review with the UN, 47 other countries raised questions or made recommendations for Australia to improve its asylum, refugee and immigration detention policies to comply with international law.

The Impact of COVID-19

The Impact of COVID-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has had disastrous consequences for people seeking protection both those in Australia and those overseas. For those in Australia, many lost their jobs or had their hour severely reduced that they had to rely on charities for basic necessities. This is because most of them worked in jobs that were hardest hit by the lockdowns such as retail, hospitality and events. They were excluded from any federal government support and were told to “go back home” irrespective of the fact that international borders were still closed and the reasons they fled in the first place still remained.

For those already overseas or between countries the closure of borders brought on by the pandemic meant a halt to many refugee resettlement programs leaving millions of people in limbo for an unspecified amount of time. While resettlement has re-started coronavirus restrictions mean that the number of refugees resettled in 2020 was much lower than initially planned despite the need being great.

For more about what you can do to support people seeking asylum and refugees during COVID-19 please donate or assist the Jesuit Refugee Service and the House of Welcome.

Turning Back Boats

Since 19 July 2013, the Australian Government has decided that no one who arrives by boat seeking asylum in Australia will ever get permanent protection as a refugee. Shortly after that, on 18 September 2013 the Australian Government began the military operation “Sovereign Borders” which forcibly turns back to their country of origin if they are carrying people seeking asylum. As at 20 July 2018, since “Operation Sovereign Borders” began the Australian Government has stated that they have intercepted and turned back , 33 vessels had been intercepted with 810 individuals on board. Boat turnbacks are only supposed to occur “when it is safe to do so” but several boats that have been turned back have run out of fuel or run aground. Despite the perception, because of Australia’s geographic isolation, the number of people seeking asylum arriving in Australia by boat is actually very small. The Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law has a useful factsheet which details Australia’s policy and practice of turning back boats and why it is in violation of international law.

Processing and Detention

“Offshore Processing”

In August 2012 the Australian Government reinstated a policy of “offshore processing” (which invariably involves some form of detention) under which people seeking asylum who arrive by boat without a valid visa are transferred to “Regional Processing Centres” in Nauru or Papua New Guinea to have their asylum claims assessed by the laws of those nations. Australia is the only country in the world to have this policy and practice.

As of 31 December 2020, the Refugee Council of Australia concludes from a number of different sources that there are still 145 people in Papua New Guinea and 137 people on Nauru.

“Offshore Processing” has led to has led to prolonged and indefinite detention and enormous human suffering, inhumane conditions, with grossly inadequate health care and consistent reports of sexual, physical and psychological abuse. Many of people have been incarcerated there for more than seven years with inadequate food, water, living conditions and access to medical and mental healthcare.

Mandatory Detention

In 1992, Australia introduced a policy of mandatory, indefinite detention under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) for any non-Australian citizen present in the country without a valid visa. Because of the persecution they face, most people seeking asylum cannot obtain a visa before they arrive. In July 2013, the UN Human Rights Committee found that the indefinite detention of these people breached the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Those who seek asylum after arriving in Australia on a valid visa are processed “onshore”, although they are frequently detained in closed immigration detention facilities until their claims are assessed. As at 3O November 2020, there were 1,518 people were held in closed immigration detention facilities in Australia.

The cost of offshore detention is extraordinarily high. The Refugee Council of Australia states that Australia’s policy of forcibly detaining people seeking protection offshore usually costs more than $1billion per year. In 2019 the report entitled ‘At What Cost?’, found that offshore detention and processing cost around $9 billion over the period 2016 to 2020 alone.

In contrast, the costs of holding someone in Australia is far more inexpensive. For example in the 2018-19 financial year, according to the figures compiled by the Refugee Council of Australia, the annual cost, per person, of detaining and/or processing individuals in Australia was as follows:

- more than $346,000 to hold someone in detention in Australia;

- $103,343 for an asylum seeker to live in community detention in Australia; and

- $10,221 for an asylum seeker to live in the community on a bridging visa while their claim is processed.

Excision

Since 2013, under Australian law, a person who arrives by boat without authorisation is barred from applying for any sort of visa, including a Protection Visa, unless the Minister for Immigration personally intervenes to “lift the bar”. As a result, asylum seekers who arrive anywhere in Australia by boat cannot apply for a visa except at the discretion of the Minister for Immigration.

‘Fast Track’

In December 2014, the refugee status determination system for people who came by boat after 13 August 2012 changed. The new process, so-called ‘fast tracking’, meant the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA) would no longer hear directly from people claiming asylum. The Refugee Council has raised concerns about the risks and lack of fairness of this process.

Processing of applications

As at 4 January 2021 there were still 4, 707 applications still waiting to be finalised with the Department of Home Affairs. The average time taken between a claim being lodged and the Department making its decision was 415 days for temporary protection visas, 316 for Safe Haven Enterprise visas and 257 days for Permanent Protection visas. As at 12 December 2020, the Refugee Council of Australia states there are now still 40, 000 people seeking asylum in our community who are still waiting for the government to decide on their refugee claims, many of whom came here more than seven years ago and have children who were born here.

Types of Protection

(Permanent) Protection Visa (Subclass 866)

This visa is only available to people who arrived in Australia on a valid visa, “engage Australia’s protection obligations” and meet the conditions of Refugee and complementary protection under the Migration Act 1958. It allows someone to live and work in Australia as a permanent resident. If someone arrived in Australia without a valid visa and did not apply for a protection visa before 1 October 2017, the Government requires them to depart Australia immediately.

The Refugee Council of Australia has an extensive and helpful section on its website about applying for refugee status in Australia how the Australian Government determines whether a person is a Refugee.

Temporary Protection

Since 2014, people who arrived without a valid visa can no longer get a permanent visa regardless of when they arrived. People either qualify for a Temporary Protection Visa (TPV) for three years or a Safe Haven Enterprise Visa (SHEV) valid for five years and have to reapply for their visa before it expires or risk deportation from Australia. Both visas allow people to work and study in Australia but a SHEV requires people to work or study in regional Australia.

There are several issues with temporary protection visas. People may never be able to reunite with their family overseas, who may also be facing persecution, making it harder to make a new life for themselves here without family support and they will never have the same rights as other Australians or permanent residents even if they spend the rest of their lives here.

Community Detention and Residence Determinations

Community detention allows people to live at a specified place (and may need to report to the authorities regularly) in the community while still officially being in immigration detention while the Minister of Immigration determines their application for a visa. They receive limited social support and access to Medicare but cannot work.

Bridging Visas

In October 2011, numbers of people seeking asylum who were held in closed immigration detention facilities were released into the community on Bridging Visas (subclass E). They may have reporting requirements and restrictions on their ability to work.

Status Resolution Support Service

Status Resolution Support Services (SRSS) is the program that supports vulnerable migrants who are waiting for the government’s decision on a visa application, including people seeking asylum. Both programs provide a basic living allowance (typically 89% of Newstart allowance), casework support and access to torture and trauma counselling. The Refugee Council of Australia has a more detailed explanation of the SRSS and the different categories within it. Since 2018 this support mechanism has progressively been cut for more categories of people who had been receiving it it as the Government no longer wishes to provide them with even this basic level of support.

Complementary Protection

Because the definition of Refugee in the Refugee Convention is limited, it does not encompass all peoples in need of protection. Countries, such as Australia, who have signed a number of other international agreements that respect human rights, such as the Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child cannot send people seeking asylum back to countries where they be arbitrarily deprived of life, or exposed to other cruel, degrading or inhuman punishment. In 2011 the Australian Government introduced a system of Complementary Protection which considers the needs of people who are not refugees under the Convention but who may face torture or other human rights violations if they are returned to their country of origin. A person’s claim for complementary protection is considered at the same time as their claim for refugee status.

However it is important to note that while the Australian government Complementary Protection which considers the needs of people who are not refugees under the Convention but who may face torture or other human rights violations if they are returned to their country of origin, in 2015 the United Nations found that Australia had breached the Convention Against Torture.

More Information and Getting Involved

- To find out more about the different conditions of people seeking asylum and refugees click here.

- To find out more about what the Church teaches click here.

- For more information and how you can get involved click here.