In October last year the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, released a vital report as part of the Paris Agreements – to keep warming to 2° and try for 1.5° – to give policy makers a clear sense of the differences between a 1.5° and 2° world and the different pathways to achieve the target. Ninety-one authors and review editors from over 40 countries put the report together along with thousands of experts and also input from governments around the world. The report brings together over 6000 scientific references as the IPCC doesn’t conduct its own research, but rather exists to bring the best research together to inform policy makers on what we do and don’t know about the risks associated with climate change. Given the hefty length of the report and the extensive press coverage it has been receiving we have put together a summary to give you a clearer sense of all the information behind headlines. You can find the full report here.

Main Conclusions

- We have already reached a rise of about 1° from pre-industrial levels. Humans are estimated to have caused approx. 1° of that warming, with a range of 0.8-1.2°. The emissions so

far released will persist for centuries to millennia and cause climate related changes such as rising sea-levels, more extreme weather events and diminishing Arctic sea-ice among others. But these emissions alone are unlikely to cause a 1.5° rise in global temperatures.

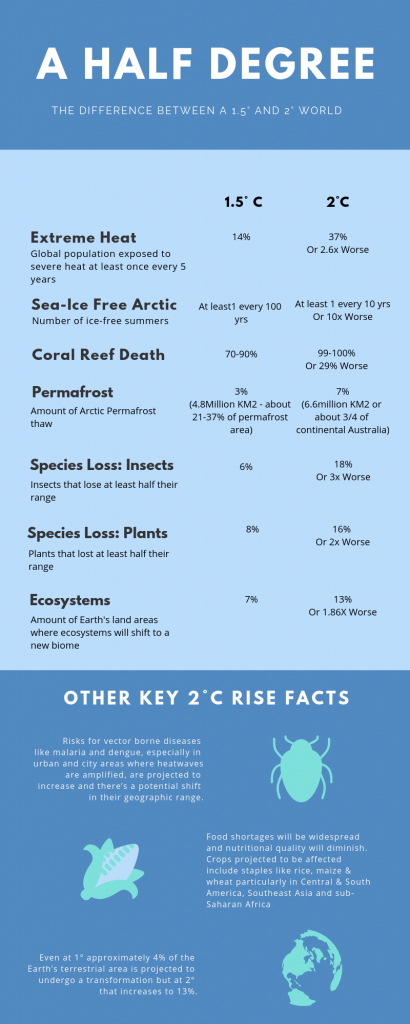

far released will persist for centuries to millennia and cause climate related changes such as rising sea-levels, more extreme weather events and diminishing Arctic sea-ice among others. But these emissions alone are unlikely to cause a 1.5° rise in global temperatures. - Every bit of warming matters – a 1.5° rise is significantly different both in outcome and in pathways to achieve it than a 2° rise. But to be clear, a 1.5° rise still poses significant risks to human life and health, economies, dramatic climate changes and for some ecosystems it may be a tipping point from which the loss or damage will be irreversible. For example, at 1.5° we will still see the death of 70-90% of Earth’s coral reefs, at 2° that will be 99%-100%.

- 1.5° is not the same for all parts of the Earth or people therefore this rise is unlikely to be safe for all. The poorest and most vulnerable, especially in low-lying regions, small island states and coastal communities will be hit the hardest and we should still expect to see from now on widespread food insecurity, forced migrations, loss of livelihoods and water supply shortages. These communities are also likely to experience more compounded and multiple risks, making the ability to adapt to or mitigate warming that much more difficult.

- Limiting rises to 1.5° is possible within the realms of physics and chemistry, but it will require ‘rapid and far reaching’ transitions in every system – land, energy, industry, transport, buildings, cities and urban planning. The scale and extent of the transformation needed is unprecedented and will need to be unlike anything we have seen in known human history. We do have the money, skill and enough policy options to make it happen – but we need the political will and our own personal willingness to undergo socio-cultural transformations.

- CO2 Emissions need to fall about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero by mid-century if we are to have a realistic chance of staying at or below 1.5°. Other pollutants such as black carbon and methane will also need to be reduced. We are nowhere near on track to meeting this target, in fact we are set to be about 50% over the target by 2030. (CO2 emissions are projected to be 52-58 Gigatonnes in 2030 – they were at 52 in 2016 – they need to be 25-30 by 2030.) If we do not meet this target not only will we be faced with the major insecurities of using carbon removal and storage technologies, as explained below, but once we go past a certain emission point the temperature rises are ‘locked in’ – meaning even with subsequent reductions a range of tipping points may be reached with irreversible consequences. Ultimately this means we must have significantly reduced our emissions well before 2030 to ‘lock in’ a 1.5° rise. This is why the widespread reporting after the Report’s release that we have 10-12 years to fix it – beyond this we are likely to well overshoot even the 2° target.

- All pathways to 1.5° rely to some degree on removing carbon from the air, but if we overshoot 1.5° and then subsequently reduce emissions, we will rely on these technologies considerably more – this is fraught with risks and uncertainties as the technology is underdeveloped and in any case the use, and success, of it at such a scale is a complete unknown and carries its own costs.

- There is no one pathway or silver bullet for emissions reductions. However, it will ultimately require a huge scale-up of investments in a wide range of mitigation options across every sector, as well as significant efforts towards adaptation systems to help people manage, where possible, the present and unfolding effects of climate change right now. The transition in the energy sector to efficient low-carbon technologies, for example, will require an annual investment increase of 12% in energy-related investments. Annual investment in low-carbon technologies and energy efficiencies requires an upscale by roughly a factor of 6 by 2050 compared to 2015 spending.

Pathways to a 1.5° Target

A suite of current options and potential options will be needed to balance lowering energy and resource intensity, rate of decarbonisation and the reliance on carbon removal. There are different challenges and trade-offs in each portfolio of choices which will need to be measured, and will be challenged, by regional, national, socio-cultural and institutional factors. Some key points from the policy recommendations section of the Report include:

- Reduction of coal is an absolute non-negotiable. In ALL 1.5° pathways coal use for electricity generation needs to steeply decline to very close to zero by 2050.

- Deep reductions in non-CO2 emissions will also be needed in ALL pathways. Methane and black carbon need to be reduced by 35% or more of both by 2050. Cooling aerosols and nitrous oxide also need to be reduced. Targeted mitigation methods used in agriculture and the waste sector will be necessary in this regard.

- Renewable energy sources are projected to supply 70-85% of electricity in 2050. In electricity generation shares of nuclear and fossil fuels with CO2 capturing and storage are modelled to increase to approximately 8% of global electricity.

- Industry will need to cut emissions by 65-90% by 2050 relative to 2010 – energy efficiency processes will NOT be sufficient to make this reduction, it will have to include transformational changes in use of new and existing technologies and practices.

- Changes in urban planning and deeper reductions in transport and building uses will be needed. A range of technical options will need to be utilised, in transport, for example, low-emissions technology must be adopted in a more widespread manner so that it comprises 35-65% of energy-use in 2050 compared with the less than 5% projected for 2020.

- Land use will need to be remodelled extensively for higher energy crops as well as a significant reforestation/afforestation increase of up to 9.5million km2 by 2050. This poses profound challenges for land-use, but mitigation options include changes towards less-resource intensive diets (more plant based), sustainable intensification of land-use practices and ecosystem restoration.

- Carbon removal is likely to be needed in any 1.5° pathway. However, these technologies are developing, so relying on them, especially in the case of an overshoot, will be inherently risky and filed with uncertainty. Options include afforestation and reforestation, land restoration, some capturing technologies like Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS – involves growing high-energy crops that can be processed to produce energy and their carbon then captured and stored underground) or various Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS) technologies. All have cost-benefits, many of which we don’t fully understand yet, and are unsure how they play out at the scale needed in any overshoot scenario.

Equity and Sustainability towards 1.5°

The other major section of the Report examines how the global transition can be managed effectively and equitably in a way that respects the Sustainable Development Goals, and thus protects the poorest and most vulnerable.

As mentioned above, the effects of a 1.5° or a 2° rise will affect poorer more vulnerable communities more deeply and quickly than developed countries, in this regard halting warming at 1.5° is obviously in their greater benefit, at least immediately. But mitigation and adaptation responses also have great potential to adversely affect those same communities. The measures we choose to take must take this into account and be mindful of further entrenching poverty or placing undue, unrealistic and unfair burdens on poorer countries to implement measures. An integrative, sustainable approach with low trade-offs or costs across regions and the globe is necessary. The majority of modelling of a 1.5° pathway could not construct one that did not involve international cooperation. For example, pathways that include low energy demand, low material consumption and low-intensive food consumption have an integrative element, or synergy as the Report names it, that has a low number of trade-offs in respect to sustainable development most notably in easing the burden on land use and allowing land for renewal efforts like reforestation or afforestation. Such an approach would limit the need for carbon removal technologies, help reduce inequality and poverty and help limit warming.

Developing economies that still rely on high fossil usage must be encouraged and assisted to implement energy diversification. We all must engage in redistributive policies, investments in infrastructure and technologies from national, private and multilateral sources that allow these economies to transition without the trade-off being poorer people getting more poverty, unemployment, disease, food and water shortages etc. ‘Social justice and equity are core aspects of climate-resilient pathways that aim to limit global warming to 1.5°’.

What can you do?

The Report makes clear that while individual consumption choices have a role to play, they will not be the key to reaching our 1.5 target. That will require national and international transformations. So one of the most important ways you can ‘care for Creation’ as our Catholic Social Teaching calls us to do, is to advocate for action on climate change at the local, state and national levels by visiting, writing and holding to account your political representatives. Consider forming or joining groups and coalitions that seek to do this. The Global Catholic Climate Movement and Catholic Earthcare Australia are good places to start your journey!